14 minute read

Stefan Leijdekkers | Treasury Executive Commercial Bank | Bank of America

Jeff Minick | National Transformative Technology Group Executive | Bank of America

14 minute read

Everyone knows tech companies are really adept at raising money. The problem is what can happen after that. Especially during their startup phase, tech companies rarely are able to hire treasury professionals who are used to managing liquidity — keeping the optimal amount of cash available for operations, while successfully investing the rest. And that can get them in trouble.

If you think liquidity isn’t a big deal — since investors are still swooning over tech companies — consider the trajectory of the past five years. Think back to 2021. “Everyone was raising money, there was a lot of money in the system — more than ever before,” says Jeff Minick, Bank of America’s Transformative Technology Group executive. “Some companies said, ‘I don’t want to raise money because it will dilute my equity percentage.’ After all, for the past five years, money had been readily available. And then 2022 hit. Interest rates rose, valuations were not where they were. And the money people had raised in 2019 and they thought needed to last only a couple of years all of a sudden had to last until 2023.”

Many companies learned the hard way that liquidity is the number one lifeblood of the organization. When a company loses money from an operating perspective, everyone understands. But liquidity is different, especially for a CFO. You can’t run out of cash.

"A tech startup needs to focus on the prudent use of capital, until there is a proven business model."

For tech companies, liquidity requires a different equation than the rules used by businesses in other sectors of the economy. “A tech startup needs to focus on the prudent use of capital, until there is a proven business model,” Minick says. “That’s critical, because there is no guarantee you can raise another round of funding.”

To begin with, the company treasurer must understand that his or her role may be different than the treasurer of a non-tech business. Explains Minick: “Tech founders are idea people. Sometimes the CFO needs to be the chief ‘no’ officer. The founder will have 10 ideas. But if capital is scarce, if you don’t have an unlimited supply of cash, the CFO should drive discipline within the organization. What are the one, two or three ideas you can chase to build that valid business model?

“That’s where we see companies fail; they lack a focus and discipline in managing their ideas and thus their capital.”

The number-one job is to put money into the core business. “That is the greatest return. That’s what you’re getting investment dollars for. That capital has been invested to be ready to grow the business,” Minick says. “And it needs to be able to last long enough to ride out cycles in the business.”

In thinking about a liquidity strategy, how much cash is enough? Bank of America’s view is that a company should have cash totaling three times its annual burn rate. So if a company is burning $10 million a year, it needs $30 million in available cash.

But Minick says most tech companies, once they’re Series B/C companies, often operate with only one to two years’ available cash. An exception: bootstrapped companies that show profit and a profitable business model. They have to raise less money but also have a slower growth rate.

For every company, the trick with liquidity is to figure out the point of equilibrium: How much liquidity do I need to achieve my optimal growth/profitable business model? It’s not necessarily difficult to figure that out. The challenge is sticking to it. “When capital is not unlimited, focus matters,” Minick says.

Many tech companies, especially at the early stage, also haven’t taken the time to construct an investment policy. Instead, investing capital often is happening fast and loose, and the founder is frequently making investment decisions for the company. “The tendency then is to default to the same type of investing profile for the company that the founder would follow personally — and often, not surprisingly, that means a portfolio that’s tech-leaning, future-leaning,” Minick says. “That is not the best solution for either liquidity or corporate investments, where you need to mitigate risk.”

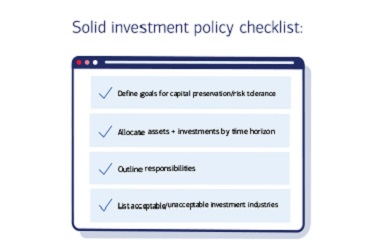

In order to stay focused on the main goal — using investor dollars to build the business — tech companies need to carve out the time to craft a solid investment policy. In general, that policy should contain goals for capital preservation and risk tolerance, allocate assets and investments by time horizon, outline responsibilities, list acceptable (and unacceptable) sectors and industries for investment.

Best practice — for true operating cash — is to maintain a minimum of seven days’ worth of operating liquidity in the operating account at a highly rated bank to ensure it is readily available if needed, without the need to convert or sell investments.

For surplus cash, a well-written investment policy for a tech company should be conservative, Minick says, generally focusing on bank deposits with highly rated banks, money market funds and U.S. treasuries — AAA-rated investments at the worst — and largely concentrated on the short term. “Why would a high-growth pre-profit tech company ever invest in something for five years?” he asks. “When you think about it, it makes no sense.”

“For a tech company, it’s all about tenor and capital preservation,” he says. “In tech, most cash is needed in the medium term or less. You should expect you are going to spend it to invest in the company. There is very rarely a place for long-term investments.”

To effectively manage capital and investments, it’s important to work with a financial institution that understands the tech industry, that understands the progression of a company from startup and Series A through an IPO.

Most tech companies are global — either in production, sales or both — so they also should consider the potential complications of global cash management.

“In managing global liquidity, the first priority is the need for visibility and control.”

Stefan Leijdekkers says, “In managing global liquidity, the first priority is the need for visibility and control. The first questions should be: Do we understand where all the cash balances are? Do we have control over our cash? And can we move it to where it needs to be?”

Leijdekkers is treasury executive for the Commercial Bank’s high-growth segments including technology, healthcare, restaurant franchises, and sponsors. For a global company, he says, it’s the treasurer’s job to ensure cash is available in the right country and in the right currency at the right time. It sounds simple but can be complicated. “There are regulations in many countries that restrict transfers and currency conversions, which can lead to trapped cash in certain markets — and inefficiencies in liquidity management,” he says. Sometimes it’s unavoidable; doing business in countries like China or India means working with strict regulations in place.

To effectively manage cash, he says, “It’s really important to stay up to date with regulations in each of the company’s markets. But that’s not easy, if, like many tech companies, you run a lean finance team or a small dedicated treasury group based in the U.S.”

It's also important to understand the strategies and tools that are available to optimize those cash balances. Companies with extensive global operations often physically consolidate their international and sometimes global surplus cash in locations like London or Amsterdam. In addition, solutions like notional pooling allow a company to offset debit and credit balances across different currencies without actual conversion. Virtual account management also can help reduce the number of physical accounts and improve reconciliation.

At Bank of America, Leijdekkers says, helping clients manage global liquidity is a very collaborative process. “We can’t just get information from a client and send back a solution; we spend time to understand the clients’ detailed liquidity management objectives; existing account structures, currencies, balances; system integrations; reconciliation needs; and tax positions,” he says.

For instance, he says, “Earlier-stage companies just beginning to open offshore sales offices, software engineering, or finance and customer support departments are often interested in automating one-way just-in-time funding for non-revenue-generating entities in APAC and EMEA.” That automation can ensure payroll and other local obligations are met without questioning whether funds will arrive on time, or worrying about local holiday bank closings.

Depending on the intracompany agreements, he says the most common scenario starts with initial funding from a U.S.-based parent company — for example, a global tech company with local subsidiaries and expenses in the U.K., Netherlands and Singapore. “The company can ask its financial partner to establish cross-currency sweeps from the U.S. to the accounts in each international subsidiary’s country,” he says. Then in a situation where it’s advantageous to keep money in one location or another — for instance, when the U.S. began raising interest rates in 2022, well ahead of other countries’ central banks — he says, “this approach can allow a company to earn a solid yield on balances in, for instance, U.S. dollars in the global header account, while also funding non-interest-bearing or even negative interest currencies like Euro obligations just in time.”

As companies grow from startup to mid-market, they may reach an inflection point where they prefer to pay in local currencies rather than U.S. dollars. Or the company might see a sizeable aggregate client base in one jurisdiction with corresponding expenses in the same currency. As a company begins collecting in multiple currencies and geographies, it will want to reconsider its liquidity approaches, Leijdekkers says, “perhaps pivoting from one-way cross-currency funding sweeps to the gold standard: omnidirectional global cash concentration. Physical cash concentration structures can be configured to hold cash within one preferred legal entity, located in a favorable jurisdiction.”

In 2024, having a well-thought investment policy and liquidity strategy is more important than ever. As the markets recover, rates start to drop and the economy steams ahead, itchy investors who have been sitting on the sidelines are ready to put their money to work. It’s an opportunity for tech companies to recruit new investors and build up cash reserves to support the next growth spurt.

“After the past three years, people have learned the lesson that liquidity is not infinite; that is evident.”

“After the past three years, people have learned the lesson that liquidity is not infinite; that is evident,” Minick says. “We went from a period of feeling that capital is infinite — to ‘Oh, no, I can’t raise money now; how long will this cash last?’”

At a macro level, Leijdekkers predicts another year of uncertainty, with two wars, disruptions by non-state actors, and consequential elections in 76 countries around the world. “That uncertainty leads to volatility,” he says. “The geopolitical tensions in the Middle East, Ukraine and Taiwan will likely continue, and lead to a more conservative investment profile on the part of most companies — emphasizing security over yield, and choosing minimal risk. I don’t think technology companies should take incremental risk to gain a few basis points of yield.”

The outcome of the U.S. election in particular has the potential to change the flow of investment dollars, affect currency exchange rates, and influence merger and acquisition activity. “From a liquidity lens, monetary policy probably won’t be affected by the outcome of the election,” says Minick. “But the outcome could influence the way the Federal Trade Commission looks at M&A, which in turn could affect valuations; if you have more M&A activity, valuations and access to capital improve.”

Beyond that, though, Minick says, the signs are almost universally positive for the economy and the availability of capital. “The U.S. economy is great,” he says. Despite persistent inflation and less likelihood of federal funds rate cuts until late in the year, there is visibility — and stability — in rates.

In terms of M&A activity, he says, “There are going to be deals done, because they need to be done — private equity needs to monetize certain investments. That then frees up cash to invest in new places. The investment dollars are out there. Private equity or venture capital, there’s plenty of money out there.”

That’s all good news for the tech industry, “as long as we don’t get over our skis,” he says. Thankfully, the markets have a good short-term memory — and it will take a while to forget the cash crunch of the past two years. “History tells you that won’t happen for another 10 years. The markets tend to remember things for about that long. Then we forget,” he says. A sound liquidity strategy and investment policy put in place now can help companies survive the next cash crunch — whenever that happens.